US measles outbreak tops 300 cases — what to know about the disease

As measles outbreaks in the U.S. continue, here's what to know about how the disease spreads, what its symptoms are, and how to protect yourself and community from the illness.

More than 300 measles infections have sickened people in the U.S. this year, as of March 14.

That's according to the latest tally of confirmed measles cases from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Some additional, probable cases have been reported in various places, but the CDC has yet to confirm those infections.

Two fatal cases have occurred this year — one confirmed and one that's still under CDC investigation. The death of an unvaccinated child in Texas marked the first measles death in the U.S. since 2015. The second death, in a person in New Mexico, still awaits official confirmation.

The 301 total measles cases across the U.S. have happened in the following states: Alaska, California, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. Texas has been hardest hit so far, followed by New Mexico.

The majority of the confirmed cases — 280, or 93% — have been related to measles outbreaks, defined as involving three or more related cases of the disease. About 95% of the cases have impacted people who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown.

About 3% of those affected had gotten one dose of the measles vaccine, meaning they were partially vaccinated, while 2% of the cases have occurred in people who were fully vaccinated, having received two doses.

As the case counts tick upward, here's what you need to know about measles, how it spreads and how you can protect yourself and your loved ones against the illness.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What is measles, and how does it spread?

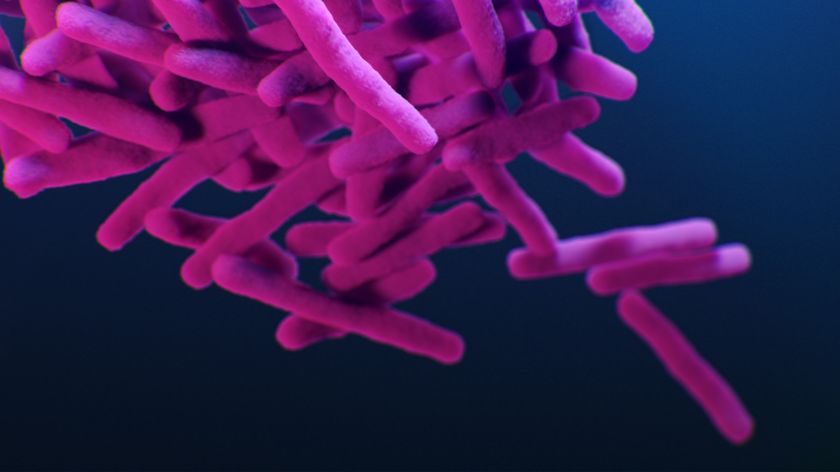

Measles is a potentially deadly respiratory infection caused by a virus known as Measles morbillivirus, or simply "the measles virus." The disease exclusively affects humans, meaning it does not infect animals.

Measles is spread from one person to another via droplets in the air, which are released when an infected individual coughs or sneezes, for example.

"[Measles] is probably one of the most contagious viruses that's ever existed," Dr. Ashley Stephens, an assistant professor and pediatrician at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, told Live Science.

Once released into the air from an infected person, droplets containing the measles virus can remain airborne for two hours. Anyone who is nearby who isn't yet immune to the virus then has a 90% chance of also becoming infected if they then breathe in these droplets. The basic reproduction number of measles — an estimate of the average number of susceptible people that an infected individual would pass the illness to — is typically cited as 12 to 18. Estimates for seasonal flu, by comparison, fall between 1 and 2.

What are the symptoms of measles, and how is it treated?

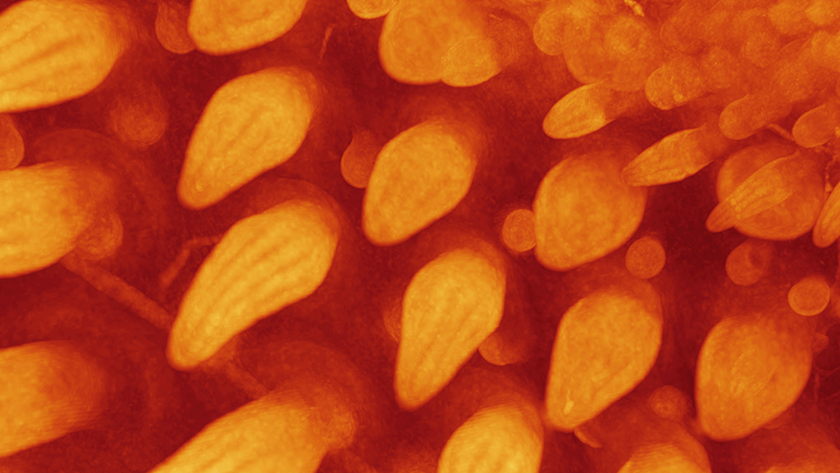

People usually develop symptoms of measles within seven to 14 days of being exposed to the virus. Common initial symptoms of the disease include a high fever, cough and runny nose, as well as red, watery eyes.

After a few days, the characteristic red rash associated with measles appears, typically first on the head before then spreading to the rest of the body. The rash starts out as flat, red spots, and later on, small raised bumps may emerge on top of the spots. The spots can end up joining together as they spread over the body.

Some people additionally get small white spots that appear inside their cheeks and on the backs of their lips, known as Koplik spots.

Measles can go on to cause serious complications, including pneumonia and swelling of the brain, known as encephalitis. These complications are more likely to happen in certain groups, such as children who are under the age of 5, pregnant people and people with weakened immune systems. Approximately 1 to 3 children per 1,000 who are infected with measles die of it, namely from respiratory or neurologic complications.

"Measles is a very dangerous virus, and many people that get infected — particularly children under age 5 — are at high risk of getting really sick from it," Stephens said.

Unfortunately, there is really no good treatment for measles, Stephens added. The disease must run its course, which normally stakes between 10 and 14 days in those who survive. In the meantime, patients may be prescribed drugs to help manage their symptoms, such as acetaminophen for pain relief and to treat fever.

For those who survive a bout of measles, they can still have ongoing health problems afterward. In particular, measles is known to induce a kind of amnesia of the immune system — people end up with immunity against future measles infections, but they become vulnerable to other germs they've encountered in the past. (This "immune amnesia" is most profound in unvaccinated people; the few vaccinated individuals that still catch measles don't suffer these same knock-on impacts.)

Related: US has already had more measles cases in 2024 than all of 2023

How common are measles outbreaks in the U.S.?

According to the CDC, 16 outbreaks of measles were reported in the U.S. in 2024, while four were reported in 2023. An outbreak, in this context, means three or more related cases of the disease, the CDC notes.

Before the measles vaccine became available in the U.S. in the 1960s, between three and four million people were infected with the virus every year, and about 500 died. Then, thanks to an effective national vaccination program and improved measles control across North and South America, measles was declared eliminated in the country in 2000. For a disease to be "eliminated," its transmission must be stopped within a specific geographical area; "eradication," by contrast, means a disease has effectively been made extinct worldwide.

Measles is still prevalent elsewhere in the world, so cases can occasionally be imported into the U.S. This can happen when people get infected with measles while traveling overseas and then reenter the country, for example. These imported cases can then spark outbreaks within the U.S.

How can you protect yourself and others against measles?

The best way to avoid getting sick from measles is to be immunized with two doses of the measles vaccine. Most often, people are vaccinated with measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, the DSHS said in their statement.

Another option is the MMRV vaccine, which also protects against varicella, the chickpox virus. However, the MMR vaccine is generally recommended over the MMRV because it's less likely to trigger fevers in children.

Children should get their first dose of the MMR vaccine when they are between the ages of 12 and 15 months old, followed by a second dose between 4 and 6 years old. The schedule for the MMRV vaccine is the same.

Teenagers and adults who have received neither dose or only one dose of the MMR vaccine are also eligible to receive it, whereas the MMRV vaccine is only approved for people up to age 12. That said, certain adults shouldn't get a MMR vaccine, including people who are pregnant.

One dose of the MMR vaccine is 93% effective against measles, and that protection rises to 97% following the administration of the second dose. Evidence suggests that people who are fully vaccinated are protected for life against measles, without the need for a booster dose.

Why is there controversy around the measles vaccine?

Stephens said that anyone who is concerned about the risk that they or their children get sick from measles should contact their doctor. Their health care provider will also be able to answer any questions concerning the MMR vaccine, she added.

"We understand that many people have found misinformation, so they might have seen something about the MMR vaccine that made them concerned," she said.

One piece of misinformation surrounding the MMR vaccine is that it causes autism — a claim that originated in the late 1990s after a now thoroughly debunked paper was published in the journal The Lancet. The paper purported a link between the vaccine and autism, but its methods were flawed, its data deliberately falsified and its author had a clear conflict of interest. The paper was ultimately retracted.

Despite the overwhelming evidence against it, the link between vaccines and autism is still used by anti-vaccine campaigners to smear the MMR vaccine — a sentiment that has previously been echoed by Robert F. Kennedy Jr, the current United States Secretary of Health and Human Services. Anti-vaccine campaign groups are also presently inaccurately suggesting that the vaccine itself is causing the current outbreak in Texas, NBC News reports.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

- Nicoletta LaneseChannel Editor, Health

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.